“Killing Machine” is one of those songs that I finished writing many years ago but just never got around to recording. Now that I finally have, the result is a weird sonic gumbo, at least to me, which matches the odd nature of the lyrics.

When I first wrote it, back in late high school I think, I was fully immersed in learning to play jazz guitar. I wasn’t half bad at comping chords and improvising solos, especially for a kid. But I also never stopped writing songs, so my rock and folk songwriting sensibilities merged with my flowering love of jazz.

Around that time, I felt like I had become a good guitar player. Like, objectively good. Not exactly pro-level, but better than most of the adults I knew, and definitely skilled enough to stand out among my peers and get invited (by a friend’s dad, so a little nepotistic) to sit in with a college jazz band during rehearsals.

I didn’t feel good about much back then. I hated school, I’d been depressed for years, and I’d long been having friend troubles that…hurt. I’d been lonely and frustrated a lot. And of course there’s all that general adolescent insecurity that piles on top of sensitive kids who are already struggling with mental health and emotional issues.

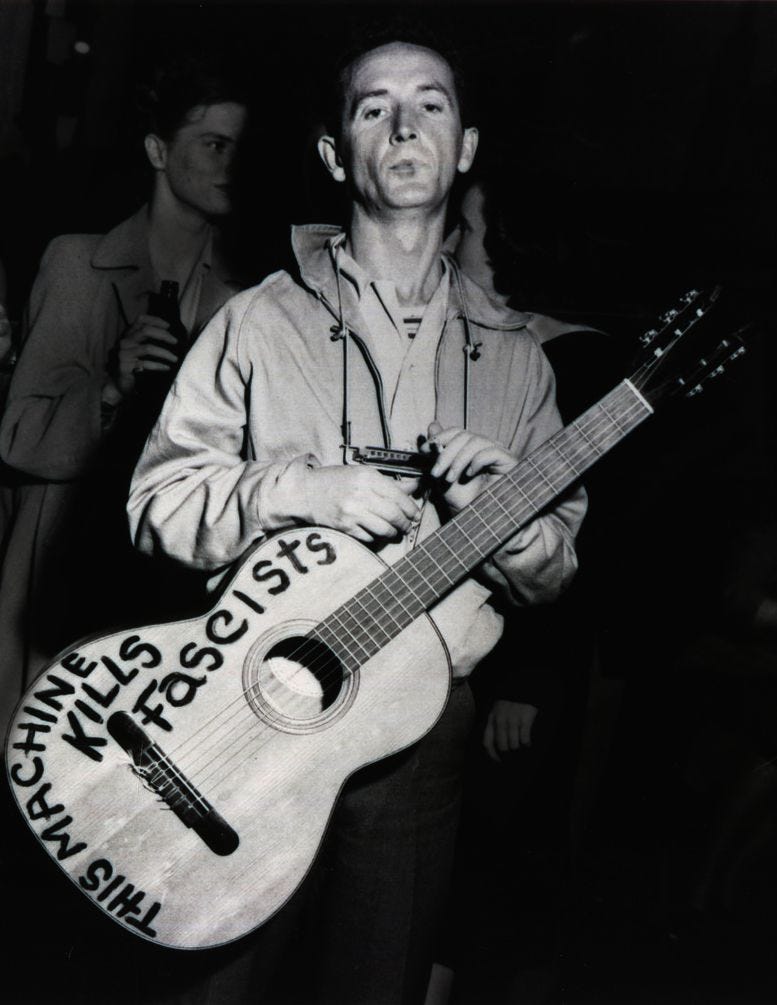

And so, knowing—or at least feeling—that me & my guitar were unimpeachably good, and I felt good when I was playing and writing, was life-giving. That’s what inspired me to write the song, I think. I’ve always loved the metaphor of a guitar as a weapon—a notion I first encountered via that iconic image of Woody Guthrie’s guitar. His flat top acoustic was covered in the words: “This machine kills fascists.”

What a perfect little piece of rebellious art. And so, feeling empowered by my skills, and protected by my old beat-up archtop that I could wield as a weapon against the demons making me miserable, I adopted the same mindset. And the parallelism of a cowboy’s six-shooter and the six strings on a guitar is just too juicy to ignore, innit? This here is a killing machine. Hence the title.

Here’s the song:

Lyrically, I tell the story of getting good at guitar. In a way, I think it was meant as a “thank you” to the genre of jazz that I’d come to love, but moreso to my awesome guitar teacher, Michael Kotur. Man, he just knew what to give me, and when, and how. He taught me a bunch of music theory and how to improvise—all stuff I didn’t know I could learn. During my senior year of high school, I lived for our weekly lessons.

The best way to describe Michael is that he was kind of a redneck hippie. You could hear it in how he spoke, but also in his overall vibe (and long hair). Chill and spiritual in a way—he was big into Tai Chi—but grounded like a good Midwesterner who knows how to work for his money and appreciates every dime of it. He always struck me as someone who knew himself well, and he seemed to have a knack for seeing things as they are. Like, he knew precisely how skilled he was. He was great. (I looked him up while writing this and found some of his more recent work online. Still. So. Good. That style—loud and full, energetic but smooth, so creative.) But he could spot a guitar player who was better, and instead of being jealous, he would remark on how great that guy was, and, I’m pretty sure, would add some new moves to his own repertoire.

And so, I believed him when he once said to me: “You can be as good at this as you want to be.”

I don’t think I can overstate how important it was for me to hear that. Especially coming from someone whose assessment I trusted. It’s a compliment that is meant to empower. You can be as good at this as you want to be. That gave me power. And control. Over something I cared deeply about. What a gift!

Humans are often driven by doubters and haters. (I’m no exception.) The voice in their head is You’ll never amount to anything or You can’t do this or perhaps it’s just ringing, mocking laughter. But Michael’s statement of fact gave me a different mantra as I worked to become a serious musician. You can be as good at this as you want to be.

The end of the song is tongue-in-cheek, almost an apology for how I went to college to study music, but in doing so I pivoted to composition—art music and classical training—and let my jazz chops atrophy. I played in the college jazz band for a year or two, but I just didn’t have room for that and everything else I had to learn. So instead of becoming the guitar player he told me I could be, and even though I realllllyyyy wanted to be that player for a time, I just took a different route. Sorry Michael. Sorry entire genre of jazz. Thank you both for everything.

Lyrics:

“You can be as good as you want to be.” That’s what he told me.

And I believed that ‘ol redneck hippie. I ran my scales, you see, until my fingers would bleed.

And I believed that I could truly be as good as I wanted to be. I studied on my archtop six string. Jazz has been good to me. Jazz has been really good to me.

My six string became the damndest thing: It was a killing machine.

And then out of the blue, I did the very thing I swore I’d never do: I walked out on you. My skills have atrophied. My fingers no longer bleed.

For the music nerds

One thing I ended up liking about the way I orchestrated this that it’s a mishmash of styles. Stuff that only sort-of goes together.

It all rests on a jazzy chord progression on an archtop guitar, but my strum pattern is unlike what one would expect on a jazz tune.

The percussion is a drum machine—a vintage drum machine that is built into an organ, no less—and it sounds like it. Quite anachronistic against the guitar. For fun and profit, I panned the drums gently left to right and back again several times to give them a little movement and depth.

So the song starts out with the oddball drum machine, then the jazzy guitar comes in, and then—harmonica? Yes. I love harmonica. And because I often play solo, I use it as a lead instrument—playing intros and solos and such to complement my singing. So why not?

And then there’s the lead electric guitar. It’s a fourth element that is slightly incongruous with the other elements. Then just as you’re confused and skeptical, I start singing, and hopefully you agree to just sit through this for a sec and see where it goes.

At some point a warm bass guitar comes in, and we’re complete.

The reason for the electric guitar becomes apparent in the C section. To understand why, let’s take a detour: The main chord progression is C6 - E9 - Am7 - Dm7 - G7. Funny enough, I came up with it while dinking on the piano. It lays real nice-like on the keys, and I remember just playing with it a lot. Then I figured out that it works just as nicely on the guitar. Kismet.

Once I started flarking around with it on the guitar, I found a nice B section: Cma7 - Cma7+5 - Dm7 - Am7 - Ab7 - G7 - Ddim7. That looks sophisticated, or at least...complicated...when you write it out like that, but it’s actually pretty simple. Move a finger here, some step-wise 7th chord action there, hit a diminished 7 chord for a flavorful turnaround, and that’s all there is to it. It’s pretty intuitive on the guitar.

So that’s all kinda jazzy. I play with those for a bit, and then the bridge (or C section, or whatever) is a different feel. I land on an A chord, and vamp. It’s more rocky and bluesy, and it’s a chance to run some scales to echo the lyrics. This is the real reason for the electric guitar. I wanted it to run the scales and also be something very different from the jazz-ish guitar, to sort of acknowledge that I moved away from the jazz stuff. I think it works.

In any case, I like it. It’s a song that I got 99% finished like 20 years ago. And I just got around to recording it all. And I like it better now than I did back then. Maybe it’s because it’s a song that had a time and place—I’m not sure I would ever write it now. Maybe I couldn’t.

Anyway. At the end of the song, I slow it all down. Fingerpicking, slow tempo. Just a little overly melodramatic. An apology.